HUMANS NOT NUMBERS

The Case for an International Mechanism to Address the Detainees and Disappeared Crisis in Syria

Professor Dr Jeremy Sarkin

May 2021

FOREWORD

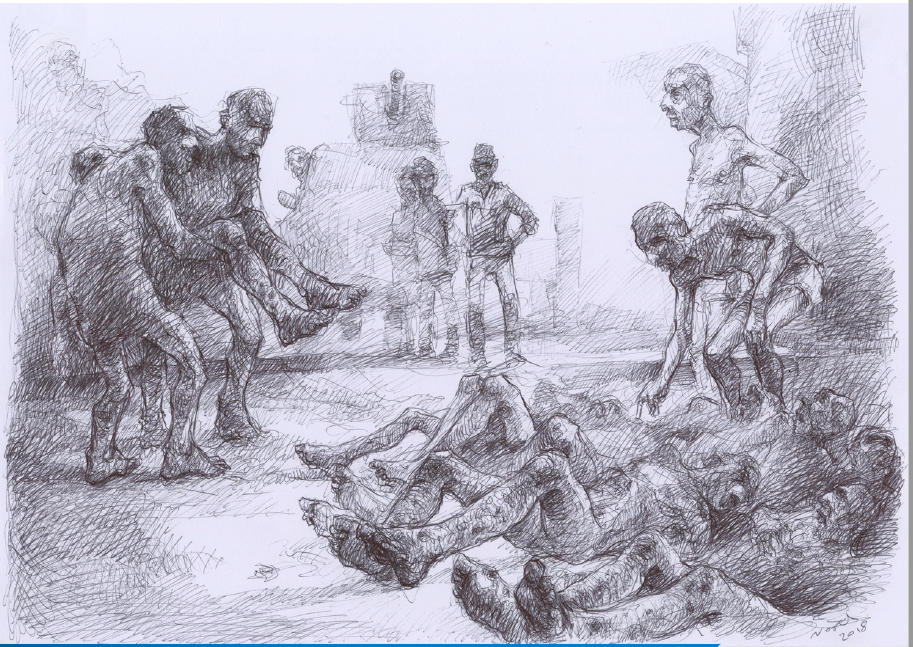

We are five associations of Syrian victims, survivors and their family members who have suffered

immeasurably from the crimes of arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, torture and many

other detention-related abuses. Like the families of the countless Syrians who have been disappeared

by all parties to the conflict since 2011 and before, we still suffer the daily pain of not knowing the

fate of our loved ones, as well as other forms of hardship resulting from their absence.

As victims and survivors, we have rights. We have therefore developed the Truth and Justice Charter,

where we lay out our vision and demands for truth, justice and the role we must play in rebuilding our

country. We have clear and achievable demands, accompanied by measures to make our vision a reality.

We must know the truth about the fate of our loved ones. Those still alive must be released immediately.

We want to receive the remains of those who have lost their lives, to give them a dignified burial

and enable us to grieve in peace. And we want guarantees that this will not happen again to

prevent others suffering what we have suffered. We have been working tirelessly for these simple aims.

But despite years of activism, documentation and international outcry, there is still no effective

body or institution that can help us discover the fate of our missing daughters, sons, spouses, parents

and siblings. We therefore requested Professor Dr Jeremy Sarkin to study the available options for

a new mechanism dedicated to this purpose. Through this study, we seek to lay out ways forward in

order to turn the support we have received from international actors into concrete action. We now

call for international cooperation to establish a mechanism to search for the missing and disappeared

in Syria, drawing on the ideas outlined in this study. After ten years of conflict, detention and

disappearance, it is time to act.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This project emerged out of a request by the following five Syrian organisations representing

survivors and victims who have suffered at the hands of various perpetrators in Syria:

• Association of Detainees and Missing Persons in Sednaya Prison

• Caesar Families Association

• Coalition of Families of Persons Kidnapped by ISIS (Massar)

• Families for Freedom

• Ta’afi Initiative

This report aims to put the goals of the five groups at its heart and ensure that any mechanism set

up to deal with the disappeared and detained is victim-centred and focuses on getting the detained

released, locating detention facilities, finding the remains of those who are no longer alive and

beginning the process of finding out what happened to them.

This is not to discount long-term justice goals such as prosecutions. As the five groups state in

their Truth and Justice Charter launched on 10 February 2021: “We… differentiate between shortterm

justice and long-term justice. In the short term there are immediate measures that must be

taken to put a halt to ongoing violations and alleviate the suffering of survivors, victims and their

families. In the medium- to longer-term we have additional demands to ensure comprehensive

justice and non-repetition of the crimes we have suffered and continue to suffer from.”7 Accountability

must eventually take its course, but the victims’ immediate priority is finding out the fate of their

loved ones.

In setting out the case for establishing a new mechanism to find Syria’s disappeared and detained,

this report seeks to shed light on the nature and extent of enforced disappearances and detentions in

Syria since 2011 and examines what help is currently available to survivors and family members. It

briefly reviews the lessons learned from how survivors and victims were traced in other conflict zones

before setting out options for setting up a new mechanism within the UN, EU or other country blocs.

Syria has not acceded to the UN International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from

Enforced Disappearance (ICED).8 Therefore, the definition in the Declaration on the Protection of all

Persons from Enforced Disappearance9 and how the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary

Disappearances (WGEID) defines it becomes important.

The WGEID defines an enforced disappearance as occurring when there is a deprivation of liberty

against the will of the person, if there is involvement of state officials – directly, indirectly or

by acquiescence – and there is refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or if the fate or

whereabouts of the disappeared person is concealed.10 For a case to be defined as an enforced

disappearance it usually needs some connection to state action but at times simply some

connection to the state – such as acquiescence by the state to the conduct of an organisation – is

sufficient.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC)11 permits any political organisation to be

prosecuted if they have committed widespread and systematic disappearances that reach the level

of crimes against humanity, as is the case in Syria.

It should be noted that even if crimes against humanity have not been committed by non-state

actors their conduct is still covered by laws on abduction, assault and kidnapping, including within

the Syrian penal code.

An enforced disappearance can overlap with an arbitrary detention. Arbitrary detentions are unlawful

in terms of a variety of international treaties and other laws. International law is clear on the right

to the truth as far as enforced disappearances are concerned and dictates there must be investigations

into those who have been disappeared and that the truth has to be sought.

Enforced disappearance and arbitrary detentions are also found in international humanitarian law,

although those terms are not used. On detentions, there are specific provisions in the Geneva

Conventions and the Additional Protocols dealing with detentions under international humanitarian

law. A variety of provisions provide for safeguards for detention during non-international armed

conflict including Common Article 3 and Article 5 of Additional Protocol II.

There is no direct mention of enforced disappearances in the Geneva Conventions or Additional

Protocols but the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Study on Customary International

Humanitarian Law12 finds that a prohibition against enforced disappearances is a norm of customary

international law in both international and non-international armed conflict13 and thus contends:

“Enforced disappearance is prohibited.”14

The methodology followed to conduct the Study was firstly a literature review to get a full understanding

of the extent of the issues and to come up with the best strategy to deal with these matters. There is

a lot of useful and recent information written by a variety of organisations about these issues.

Secondly, interviews and discussions were held with a variety of people who are knowledgeable

about the situation regarding Syria in general and the disappeared and detained specifically, including

the ICRC, the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), the UN Working Group on

Arbitrary Detention (WGAD), the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntarily Disappearances

(WGEID), the UN International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM), a variety of international

lawyers, people who have worked on these issues in a variety of settings and countries, a number

of academics, a number of Syrian organisations, international and domestic human rights organisations,

and others. The five organisations who requested this study were consulted throughout the process.

Next, a lengthy questionnaire was sent to Syrian documentation organisations to measure the

extent of the information they have collected, how many people they have details for, the type of

information they have on these people and how that information is collated and systemised. Then

analysed were the means available – and their limitations – for the families of the disappeared and

detained to obtain information, truth delivery and redress. Again, readings and discussions were

held with other groups involved in the work to understand what exists and their limitations.

In this way, the roles played by a variety of institutions including the UN Commission of Inquiry

on the Syrian Arab Republic (COI), the IIIM, the WGEID, the WGAD, the ICMP and the ICRC were

explored to understand what these institutions do at present and to understand what cooperative

role these processes could provide to a future mechanism.

This report argues that a new mechanism should be created as a matter of urgency and that it

should immediately start work on identifying ways to get the detainees released from custody and

find information on others who were detained but whose whereabouts is unknown.

To do this and provide the families with access to the truth, the mechanism must search for

information on detainees and the disappeared including collecting and collating all information

that is already widely available but not used for this purpose.

The report argues a mechanism could be set up by the UN, by the EU or by a number of states. If

created outside the UN, the mechanism should have a board made up of representatives of the

ICRC, the ICMP, the WGEID, the WGAD and a representative or two from Syrian groups elected

annually to represent victims and survivors. Such a board could still help to make it more skilled,

representative and legitimate regardless of whether it was created by the UN or not.

As noted in the aims, it is hugely important to the families that any newly created mechanism

focuses on getting the detained released, locating detention facilities, finding the remains of those

who are no longer alive and beginning the process of finding out what happened to them rather

that pursuing prosecutions and other longer-term justice processes. It must be stressed that this

type of process is also more likely to get support from a multitude of relevant actors. Uncovering

the truth can lead to justice in a variety of ways, not least that the information collected can be

useful at a later date – if so desired – for other justice purposes.